[THE DEBRIEF] 2025 HONDA CB1000 HORNET SP TRACK TEST

Did Honda build a better Yamaha FZ1?

There I was, sitting on a 2009 Yamaha FZ1 at the start/finish line of Miller Motorsports Park, now known as Utah Motorsports Campus. The naked liter-class inline-four had less than 2 miles showing on the odometer. I was staged alongside journalist and fellow racer Nick Ienatsch, who also was astride a fresh FZ1. We were both nervous, and it showed.

Let me set the scene: We were about to launch the newly formed Yamaha Champions Riding School in front of tens of thousands of rabid WorldSBK race fans. Neither of us had ridden these bikes, which were completely stock, down to the tires. On top of all that, we were both carrying passengers. There was no time for a warm-up lap and zero room for error.

By the third turn, Nick and I were inches apart, swapping positions, scraping footpegs, and laughing inside our helmets. The FZ1 felt incredible. I was instantly hooked, and the bike quickly became one of my favorites. During the past 16 years, I’ve logged more than 50,000 track miles on FZ1s. In fact, I still have a super-clean 2012 model in my garage.

For many years, the FZ1 was my definition of a “do-it-all” motorcycle. It was a total pack mule, in that it could handle an insane level of racetrack mileage, carry a passenger with ease, deliver bulletproof engine reliability, and even crawl around the circuit at parade pace, yet still rip off a fast lap at near-pro-level speed.

Over the past couple of decades, I’ve ridden and tested nearly every naked bike manufactured, including a three-year stint on a mildly modified Yamaha FZ-10. My testing window is admittedly extreme, but that has given me a sharp sense of what works and what doesn’t, when it comes to a track-focused, all-around motorcycle.

So, when Honda released the 2025 CB1000 Hornet SP, I couldn’t wait to throw a leg over it. Thanks to Nate Phipps at 2 Wheel DynoWorks, I got my chance: two full days of lapping at the Ridge Motorsports Park in Shelton, Washington, during a Ken Hill Motorsports Fundamentals Masterclass. On paper, the Honda checked every box, so I was more than ready.

My history with the FZ1 (and FZ-10) shaped how I judge every naked bike that has followed in its wheel tracks. The Yamaha is the standard for reliability, versatility, and the ability to deliver both fun and outright performance. I wasn’t merely curious about Honda’s latest effort; I was measuring it against years of testing and teaching on bikes that earned my trust the hard way.

The Hornet SP that Nate supplied is owned by 2 Wheel DynoWorks and used to produce and hone its ECU tuning, along with various intake and exhaust upgrades. For my first outing, the bike featured a soon-to-be-released ECU tune, a complete Dominator exhaust, and a fresh set of Michelin Power Cup 2 tires. Oh, and handlebar risers; Nate is 6-foot 9, a foot taller than I am.

I rode the Hornet exclusively during the masterclass school at the Ridge. The curriculum is based around alternating 40-minute classroom and riding sessions, guaranteeing a lot of time on the bike in every imaginable scenario, along with the opportunity to dial in the chassis and suspension to my personal preferences.

Enough backstory. Let’s ride.

Other than setting the tire pressures, I left the bike 100% stock, with the suspension set as it was delivered from the factory and the electronics in “Sport” mode.

First impressions:

Brakes have little-to-no initial bite, and ABS was active even at a relaxed pace

Chassis is incredibly nimble, quick steering with good stability

Engine is quick-revving, pulls hard to the rev-limiter, and is really playful

Bike feels wide when you first sit on it, but that feeling disappears as you ride

Riser-equipped handlebars are tall but easy to get used to after a few laps

Suspension is soft, soft, soft, even at a slower track pace, with little feel or support

Quickshifter suffers from too much delay, but auto blip is great

I spent the rest of the first morning and afternoon stiffening the fork and shock, concentrating on building support under braking and acceleration. Once I had a decent feeling, I worked on the geometry to bring back feel and stability.

What I felt and changed:

Fork: Straight off the showroom floor, the Hornet’s 41mm Showa SFF-BP fork is very soft and lacks any sort of control at track speeds. I added more spring preload, as well as compression and rebound damping. By the end of the first day of testing, preload was nearly maxed-out, along with compression.

Adding enough rebound to control how quickly the fork bounced back after initial brake release created issues elsewhere on the track. For example, the front tire began to tuck when I picked up the throttle, and I discovered newfound instability over rises. I never quite found a happy medium.

Shock: Starting with the factory setting, the Öhlins-manufactured remote-reservoir shock lacked high-speed damping control and was upset by quick directional changes. I added one turn of preload, but to get the support I wanted, I had to increase compression and rebound beyond the usual envelope of a higher-end TTX shock.

While this change worked to a degree, it also required deliberate and smooth steering inputs. Once the shock blew though its stroke, though, the chassis was prone to aggressive oscillations.

Geometry: I raised the fork 4mm to take weight off the front and increase trail for more stability. This, combined with the stiffer fork setting, let me brake harder and later. I went faster, but the sensitive ABS intervention reared its head even worse with the deeper corner entries. Everything is a compromise, especially at the racetrack.

Day 1 impressions:

I love this engine. Whatever 2 Wheel DynoWorks did to the ECU for wide-open performance is fantastic. The 1000cc inline-four revs eagerly and pulls cleanly to redline—lap after lap. Is it crazy fast? No. But is it fun fast? Hell, yes.

I would have preferred slightly softer initial throttle mapping, specifically 2 to 15% (which 2 Wheel DynoWorks has since addressed). The flip side is the clean way in which the engine responds at mid-to-high rpm. It’s a real joy to use, even if this was only the first track outing for the beta ECU tune. You can’t wait to grab gears.

After I tweaked the fork and shock, the chassis was working well enough that I quickly began to run short of cornering clearance. Whenever I attempted to up the pace, the toes of my boots and the ends of the footpegs ground into the pavement.

I used the dash menu to adjust the quickshifter and engine braking. From what I can tell, the quickshifter works through effort, not time. I also bumped up engine braking. That change was more subtle, but I felt a difference. Early on, I completely turned off traction control.

While powerful, the brakes have little initial bite. ABS, however, is the main issue. The chassis is begging to get into corners deep, but immediate and intrusive ABS intervention spoils the show. And no, you can’t turn it off or remove a fuse.

In fact, the issue was so severe that sometimes when I went to the brakes and built pressure the ABS came in so hard that the bike would shoot forward. Then, the brakes were reapplied hard enough that the rear wheel came off the ground. Yikes…

Once the shock was properly loaded, mechanical grip exiting corners was excellent. Similarly, with the modifications to the fork, the front tire offered great feedback from turn-in all the way to the slow point of the corner.

Day 2 impressions:

Day 2 was dedicated to fine tuning. I tried a few more suspension tweaks but ended up at the same place. Other changes caused a front-to-rear imbalance or a small improvement in one area that made the bike worse in others. I also worked on different braking applications to avoid engaging the ABS during corner entry, but the inconsistencies remained unnerving.

Over two days at the Ridge, the Hornet endured more than 15 two-up rides at a “learning pace,” a few quick laps with fellow track-day instructor Mark Price on his very quick 2 Wheel DynoWorks Triumph Speed Triple, as well as a full-bore throwdown at the end of Day 1 chasing a personal-best lap time.

What would I change?

Brakes: The ABS has to go. There is lap time lost not only in performance but confidence. I would also spec a proper, track-specific brake-pad compound.

Rearsets: Cornering clearance was second in line for my brain space, right after the ABS. Much higher entry and mid-corner speeds are achievable with additional clearance.

Remove the handlebar risers: Sorry, Nate! Yeah, I know the bike doesn't come with those risers, and the difference wasn’t terrible, but I want a lower riding position.

Suspension: The fork isn't too bad, but the shock has serious issues. I would look into rebuilding and revalving the shock for more comfort and control.

Engine: This may come as a surprise, but I would leave it alone, at least in this configuration. OK, I wouldn’t complain if there were 5-to-10 more horsepower, but it doesn’t really need it. Nate’s tuning work paid off.

Chassis: I probably wouldn’t change anything. I absolutely love the way the Honda turns. It is effortless, with a ton of feedback.

Gearing: For the Ridge, given how well the tuned, quick-revving engine runs, I probably would take a tooth off the rear sprocket to extend second and third gear.

Wrap it up:

I realize this is a different type of test. I’m not delving into brake-caliper piston dimensions or the number of available USB ports. You probably have a better idea of those specs than I do. Rather, this is about my experience in a very narrow and extreme environment.

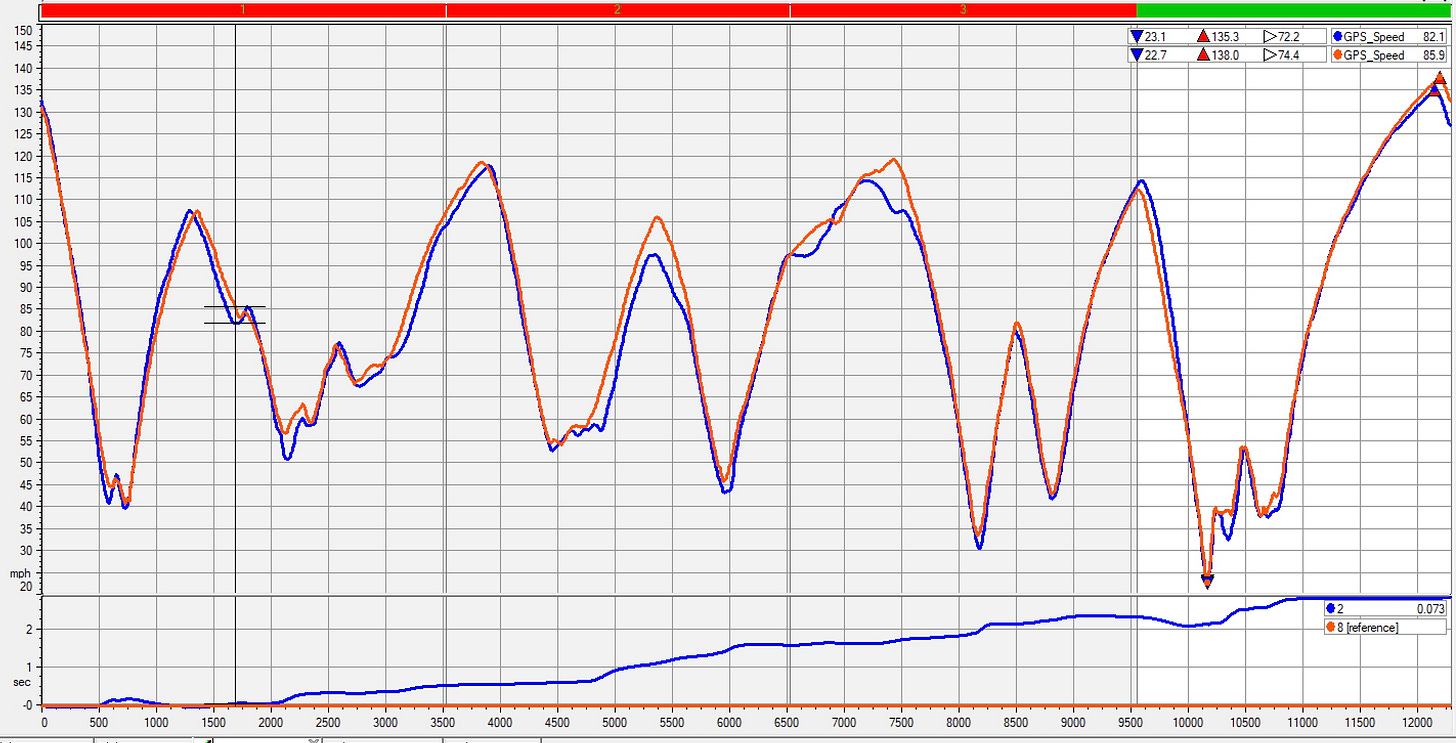

Overall, I like the Honda. It has great potential to be a very quick and comfortable track bike. Compared to my trusty FZ1, it’s 3 seconds per lap slower. But that’s after thousands of laps on the FZ1 at its absolute peak. The CB1000 is still waiting to be unleashed.

Would I buy one? The short answer is, yes. The FZ1 I rode for comparison had no electronics, no quickshifter, and was stock except for a slip-on muffler and Dunlop Sportmax Q3s. If I had ridden the CB1000 in that configuration, it would have gotten punched in the face.

You can’t blame Honda for having to meet tougher emissions and noise regulations, but to match the FZ1 in stock form will take some simple modifications. Ultimately, though, there is a better overall package waiting to tackle whatever is thrown at it.

Watch the accompanying video where I break down the timed laps between the Honda CB1000 Hornet SP and a Yamaha FZ1.

About Ken Hill

Ken Hill is considered the top motorcycle riding coach in the U.S. He bought his first motorcycle at age 30 and began road racing the very same year. Despite the late start, Ken went on to set track records and win class championships before making his professional debut in the AMA Superbike class, where he finished in the top 10 at age 41. Ken’s passion for learning and, ultimately, bettering the sport, led him to retire from racing in 2007 and devote himself full-time to coaching. Learn more at khcoaching.com.