[THE DEBRIEF] BIKES VERSUS CARS—THEY’RE COMPLETELY DIFFERENT ON A RACETRACK, RIGHT?

What are the real differences between driving and riding? Bikes and cars are more similar than you think

As a motorsports coach who works with both car drivers and motorcycle riders, I often find myself on the receiving end of a frequently asked question: “You’re a bike guy. Bikes and cars are totally different. How can you teach both?”

My first love has always been cars, but my on-track journey began with motorcycles. When I finally got to spend time in a car on a racetrack, I assumed the learning curve would be steep. After all, the controls, sensations, and techniques are completely different, right?

I give full credit to my former Yamaha Champions Riding School colleague Nick Ienatsch for shattering that assumption in about five seconds. Nick, who is an incredibly accomplished racer, author, and instructor, and also happens to be wickedly fast in a car, made the transition simple.

When I asked him how to approach driving, his answer was immediate: “Everything is the same. Drive like you’re riding a bike; just trade lean angle for steering-wheel angle.” That was it. No complicated explanation, no long technical breakdown, just a clean translation.

Nick gave me confidence that I could do it, and since then, decades of car track time, decoding thousands of data files, interviews with top-level driving coaches, and tens of thousands of laps—both driving for myself and instructing—have only reinforced that belief.

Yes, there are differences, some of which are important, but they are far smaller than most people imagine. First and foremost, the fundamentals—the things you should be doing whenever you are driving a car or riding a motorcycle—don’t change.

Vehicle placement is still king and determines outcomes

Vision skills are vision skills; references and eye timing don’t change

Motor controls create adjustability by managing weight transfer and contact patches

Brake adjustability still shapes entry speed and steering

Turn-in point and turn-in rate continue to dictate where you end up in a corner

Body position and body timing matter, for both bikes and cars

The slowest point of the corner still defines the sport

Handlebar or steering wheel, you are managing the same physics, grip budget, and human limitations. The tool has changed, but the degree of application and priorities haven’t. Once you realize this, bikes and cars stop feeling like separate worlds and become different dialects of the same language.

Let’s break down the following AIM speed graphs comparing cars to motorcycles to understand what aspects are similar and where the differences lie. First, let’s focus on a couple of car-versus-car GPS speed graphs to determine if the same fundamentals hold true for different cars running at a similar on-track pace.

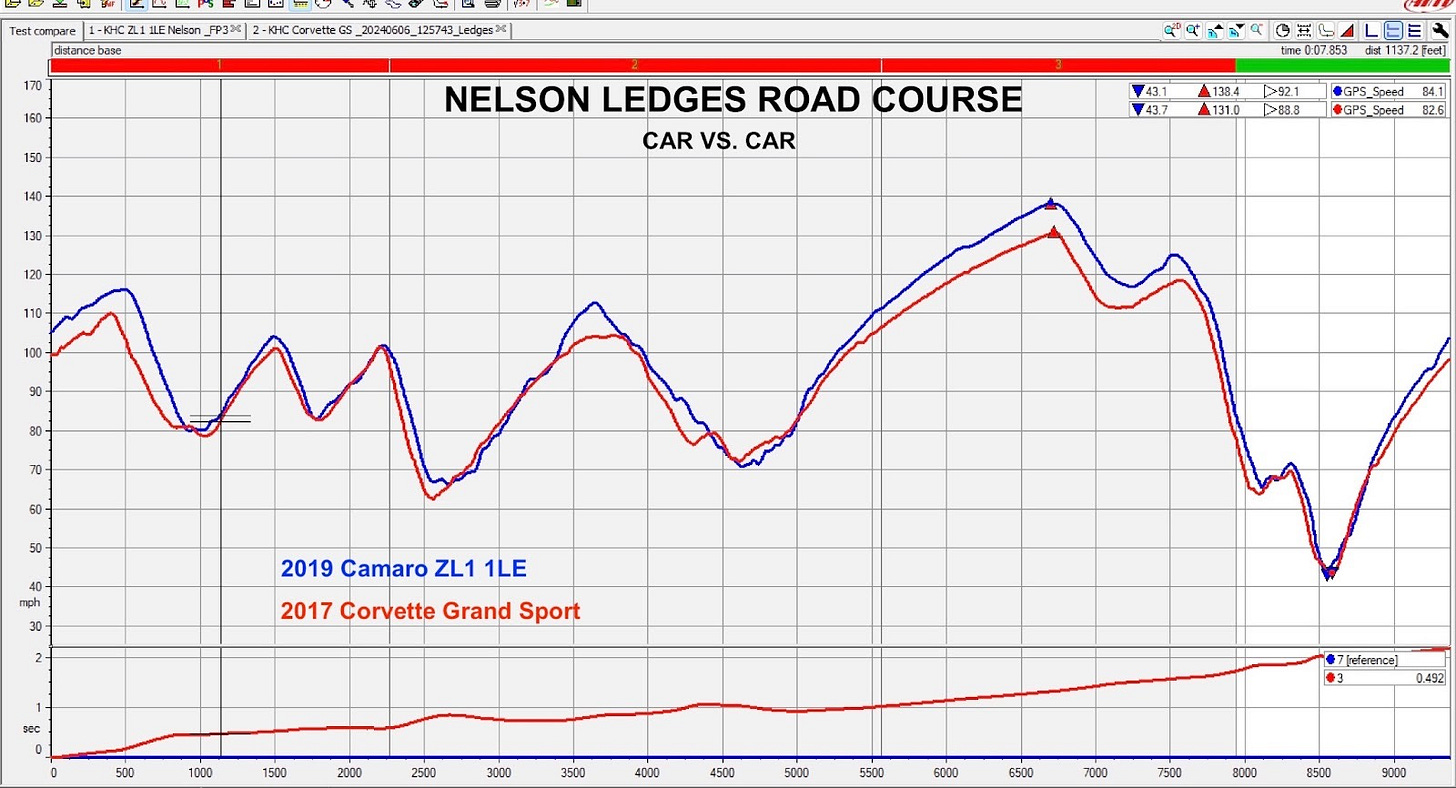

The first graph represents a 2017 Chevrolet Corvette Grand Sport (red) vs. a 2019 Chevrolet Camaro ZL1 1LE (blue) at the 2-mile-long Nelson Ledges Road Course in Garrettsville, Ohio. Both cars were in near-stock configurations running under 1-minute, 11-second lap times, which puts them at the sharp end of the advanced group.

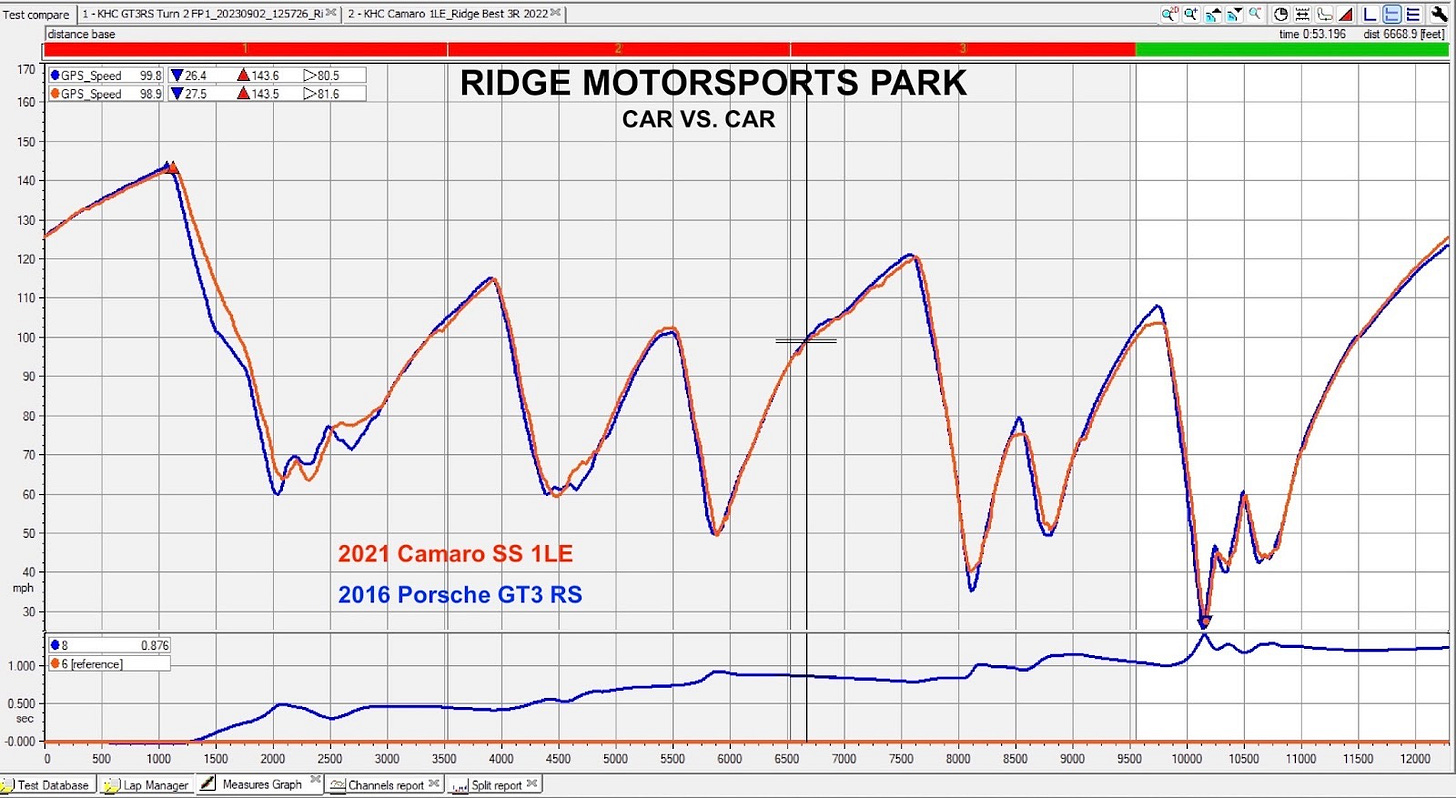

The second graph shows a 2016 Porsche GT3 RS (blue) vs. another Camaro, a 2021 SS 1LE (red), at the Ridge Motorsports Park near Shelton, Washington. Both vehicles were track-prepped and lapped the 16-turn, 2.47-mile road course in less than 1 minute and 46 seconds, which is also at the sharp end of the advanced group.

Highlights

Overall shapes are near identical

Slow-point position remains close to the same and only changes based on driver inputs and/or individual vehicle mechanical differences

Main difference is how they get to and from the slow point, regardless of different acceleration and top speeds

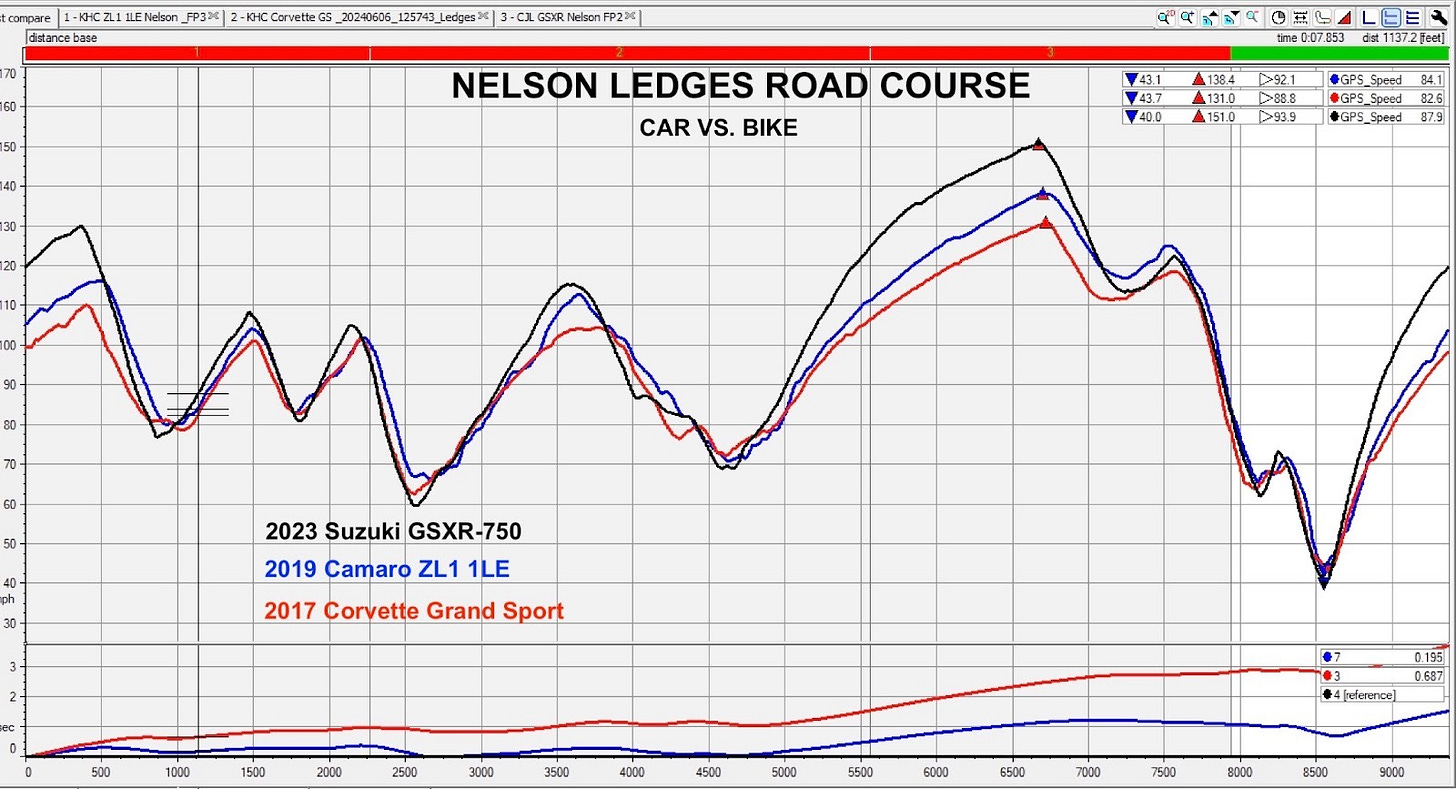

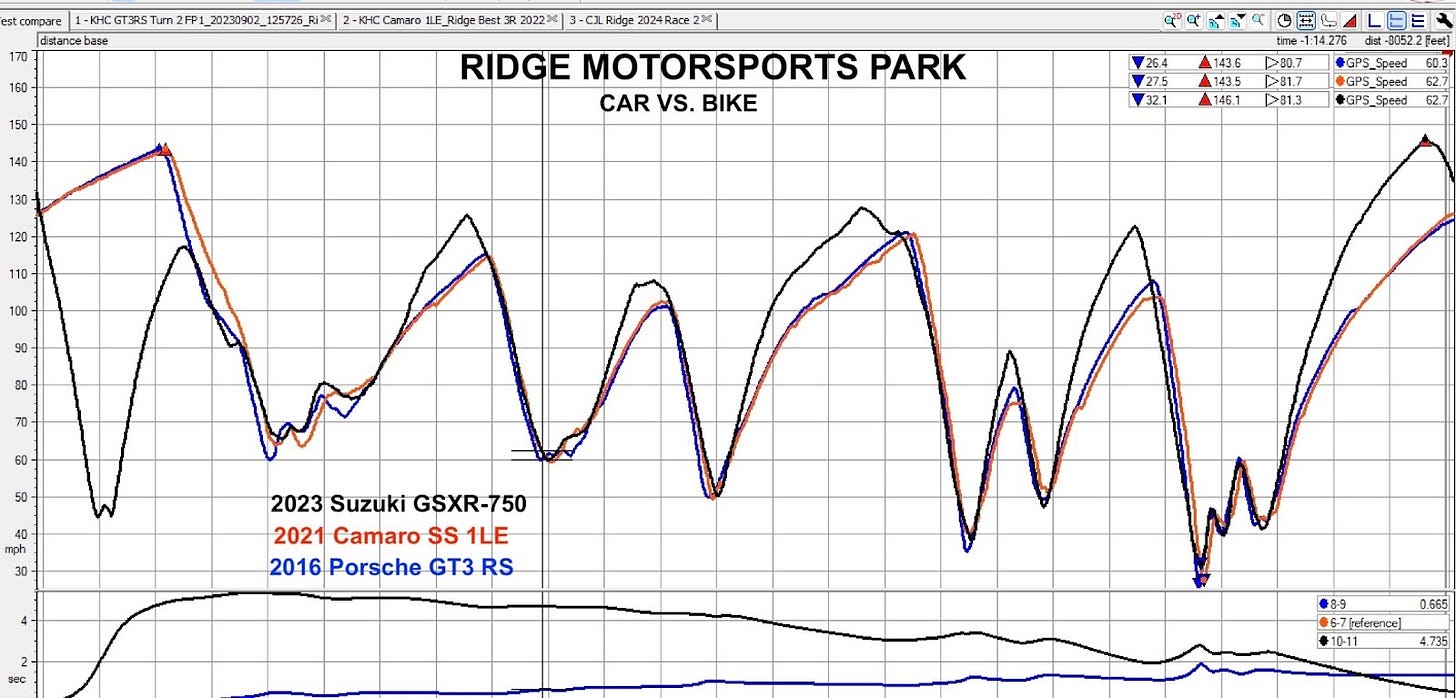

Now, let’s introduce a bike at four tracks with wildly different characteristics. Let’s start with the same venues, Nelson Ledges and the Ridge, retaining the graphs for the cars. Note: Whereas bikes use the chicane at the Ridge, cars do not. The 2023 Suzuki GSX-R750 (black) was prepped to MotoAmerica Supersport Next Generation spec and ridden by a professional racer.

Highlights

Right out of the gate, the acceleration of the bike is staggering

Bike brakes earlier, partly due to its higher top speed

Bike relies on a more vee-shaped slow point due to its smaller tire contact patches

Slow-point positions are nearly the same, with the bike’s slow point coming slightly later

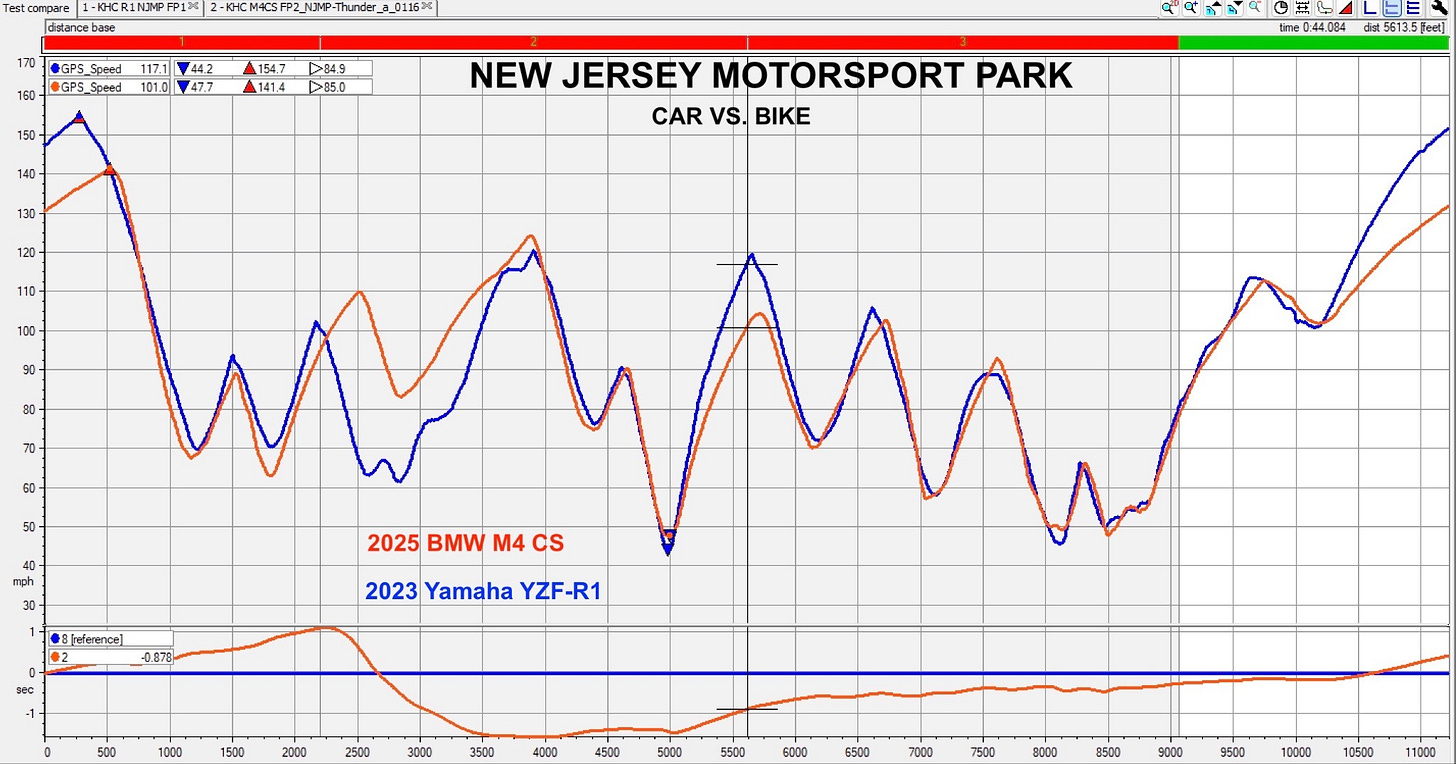

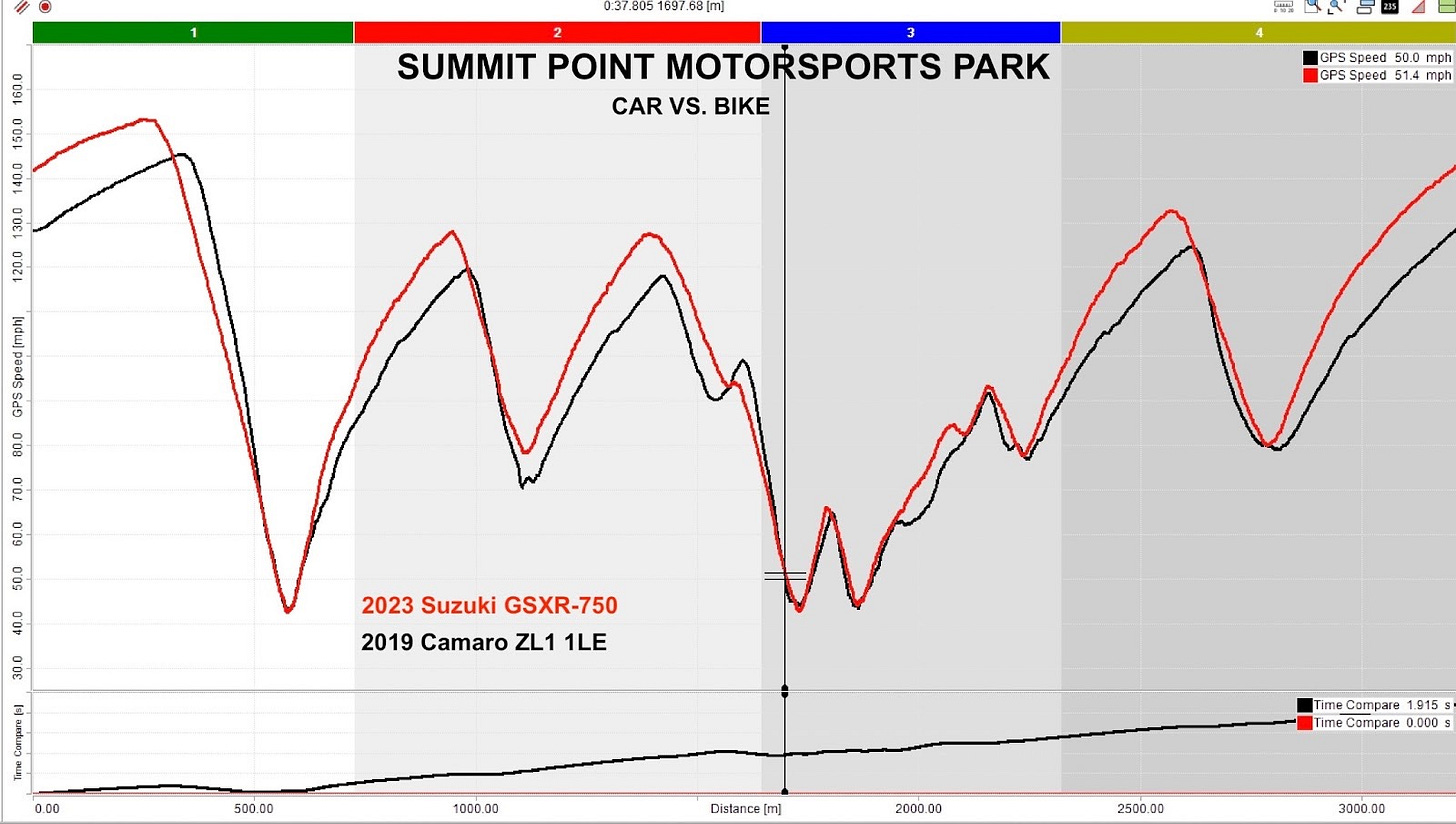

Finally, let’s look at two more tracks, again very different: 12-turn, 2.25-mile Thunderbolt Raceway at New Jersey Motorsports Park in Millville, New Jersey, using a 2025 BMW M4 CS and a 2023 Yamaha YZF-R1 (bikes utilize the Turn 3 chicane), and 10-turn, 2-mile Summit Point Motorsports Park located in Summit Point, West Virginia, again with the Camaro ZL1 1LE paired with a 2023 Suzuki GSX-R750.

Lap times at both tracks were at the sharp end of advanced pace, circulating under 1 minute, 30 seconds at NJMP and 1 minute, 20 seconds at Summit Point.

Highlights

Acceleration and top speed of the mid-displacement bike compared to the high-powered cars are mind-blowing

Slow-points positions and minimum speeds of the bike remain close to those of the cars

In some corners with exits that open up, the slow point for comes earlier and the bike carries more speed

I referenced high-performance production vehicles, but what about less-powerful machines, open-wheel cars, and prototypes? Trends remain the same. Less-powerful bikes and cars produce nearly identical graph shapes, just at lower speeds. Open-wheel cars and prototypes can carry higher slow-point speeds and often reach them slightly earlier, but the margins are surprisingly small.

Major Differences Between Bikes and Cars on Track

Contact Patch and Weight: A car has a significantly larger total contact patch than a motorcycle—on the order of 500% greater—which gives it higher absolute-grip potential in both braking and cornering. A significant portion of that grip, however, is consumed simply supporting the overall mass of the car.

Power-to-Weight Ratio: A motorcycle’s power-to-weight ratio is massively superior to nearly all production cars. This dramatically changes how quickly inputs translate into acceleration and direction changes, as well as the precision those inputs require.

Coaching: Motorcycles generally are more difficult to coach and take longer to see improvements. Cars, by contrast, allow instructors to share space and time, experiencing the same feel references in real time through right-seat coaching, which accelerates learning.

Vehicle Placement: The most important reference for going fast safely is largely the same between bikes and cars, with nuances driven by corner radius and corner length. The intent—where the vehicle needs to be on track and why—does not fundamentally change.

Vision and Focus: Vision strategy is nearly identical. The primary difference is that motorcycles provide a much larger inventory of feel references and a heightened sense of speed, both of which influence perception and decision-making.

Motor Controls: These are conceptually the same, but motorcycles demand more deliberate and finer inputs due to higher power-to-weight ratios and smaller contact patches. Errors are magnified more quickly.

Brake Adjustability: This is a major difference. During braking, a motorcycle’s fork compresses, sharpening geometry and increasing steering response and feel. This dynamic geometry change plays a significant role in how a bike turns and communicates grip.

Turn-In Point and Turn-In Rate: These remain fundamentally the same. The timing and rate-of-direction change still dictate where the vehicle sets up the entry, slow point, and exit.

Body Position: Another major difference. On a motorcycle, rider mass has a profound effect on braking, turning, acceleration, and available lean angle. It’s common for the rider to account for 50% or more of the bike’s total weight. Imagine being able to move 50% of a car’s mass in real time, which would dramatically alter the dynamics everywhere on track.

Shared Similarity: One key similarity between bikes and cars is the importance of proper ergonomics, being positioned correctly to support effective motor-control use. Excess weight on the arms or hands is a problem in both bikes and cars, degrading feel, control, and consistency.

Taking Advantage of Extra Grip: A car’s larger contact patch is most apparent in the final 50 feet of deceleration. By this point in corner entry, the platform has settled and the tires are fully engaged. That extra grip allows a driver to finish establishing direction with steering-wheel angle while still carrying roll speed, something that is far easier to achieve in a car than on a motorcycle.

Conclusion

John Surtees, Jeff Ward, Scott Russell, and Valentino Rossi are just four examples of champion motorcycle racers who went on to have genuine success in cars. Not because bikes and cars are the same, but because the process is the same. I’ve spoken with Ward and Russell about their accomplishments, and the answer is always the same: The tool changed, but the fundamentals didn’t. Vehicle placement, vision, motor controls, and using the brakes still decide the result. Master those and the platform becomes secondary.

About Ken Hill

Ken Hill is considered the top motorcycle riding coach in the U.S. He bought his first motorcycle at age 30 and began road racing the very same year. Despite the late start, Ken went on to set track records and win class championships before making his professional debut in the AMA Superbike class, where he finished in the top 10 at age 41. Ken’s passion for learning and, ultimately, bettering the sport, led him to retire from racing in 2007 and devote himself full-time to coaching. Learn more at khcoaching.com.

Great article! True test of mastery of the fundamentals is the ability to apply them in different areas. I like to focus on my brakes as I drive my truck around often slipping past the posted or recommended speed as I carry my brakes to the slowest point. As I approach the “limit” I worry more about the weight shift in the vehicle that would cause it to tip more than I do about sliding from a loss of grip.

Nice piece, Ken. I started my racing life with sprint karts in the mid-70s, racing competitively for ten years, and winning a national championship. Switched to roadracing bikes after a few years off, raced 9 years, yielding two national championships. Another few years off track and then raced Spec Fords and Formula Fords with the SCCA for 8 years. No championships but many wins and podiums in Nationals. Took a few years off and returned to motorcycle racing at the age of 65, netting two more national championships.

I agree with you about all the similarities you noted but I've also experienced differences. I've found that nearly anyone can be taught to drive reasonably fast, within 5-6 seconds of the track record for their "class", if they are willing to spend to have the best equipment and be trained. Going fast on a motorcycle is not nearly as accessible, even with training and the best equipment. Fitness is more important, and dealing effectively with uncertainty and fear seem to play a much larger role. I've never been 6-7 seconds a lap faster than another racer in comparable cars, but it happens frequently with bikes, even with inferior equipment. I'm comparatively much better on two wheels than four. Part of it, for me, is the more physical elements of riding a bike; you're not strapped in and you're moving around almost all of the time. As someone who is a fairly aggressive pilot, my aggression seems to "fit" better with two wheels than four.

I'm curious if you've had similar observations or not and, if so, to what you attribute the differences.